|

The pattern Jung-Geun consists of 32 movements and is required

for advancement from 4th geup (blue belt) to 3rd geup (high blue belt). This

pattern is named for the Korean patriot An Jung-Geun (1879-1910). The 32 movements

of this pattern represent Mr. An's age when he was executed by the Japanese military government occupying Korea in 1910.

|

| Japanese artillery unit passing through Korea |

Very little is recorded

about An Jung-Geun's life. He stepped into the spotlight of Korean history only

briefly, but left his mark as one of Korea's most revered patriots. His

story is best understood in the context of the turbulent political climate of the times.

|

| Hirobumi Ito |

An Jung-Geun was born in 1879 in the town of Hae-Ju in Hwanghae Province. An's

family moved to the town of Sinchun in Pyongan Province when he was about ten years old.

He became a well known educator and established his own school called the Samheung (Three Success) School. His school, like others at that time, was destined for hardships under the Japanese military occupation

of Korea, and it became enmeshed in a Japanese power play by virtue of its location.

In 1895 the Japanese government was determined to create a large empire that would include Manchuria and China. Korea was obviously necessary as a stepping stone for creating this empire. However, the Korean government at the time was under the indirect control of the Russian government. The pressure created by this political situation caused considerable unrest in Korea. Rising tension resulted in several meetings from 1896 to 1898 among neighboring countries

as well as foreign powers concerned about Korea's future. These meetings, which

included Japan, China, Russia, England, and the United States, resolved very little.

|

| Japanese Troops in Korea |

|

| Korean Freedom Fighter in Manchuria |

Korea was pulled further into

the conflicts when turmoil erupted in China in 1900. Chinese patriots, fed up

with colonial domination of their country by foreign powers, incited the Chinese population to a wave of violent riots known

as the Boxer Rebellion. In response to this rebellion, the colonial powers descended

upon the region in force to protect their interests. Prompted by the movement

of Russian army units into neighboring Manchuria, England established an Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902. A Russian-French Alliance was subsequently established in 1903, followed by a movement of French and Russian

troops into northern Korea. The Japanese, meanwhile, saw this action as a direct

threat to their claim on Korea and demanded the removal of all Russian troops from Korea.

When Russia rejected her demand in 1904, Japan initiated a naval attack and declared war. Korea, of course, claimed neutrality but was invaded none the less by Japan. By the autumn of 1905, Russia had surrendered and Japan was firmly established in Korea. This

invasion, however, was not viewed as an act of aggression anywhere in the world, except in Korea.

|

| An Jung-Geun |

The long-term occupation of Korea also involved the complex takeover of the Korean government. One of Japan's

leading elder statesmen of the time, Hirobumi Ito, became involved in masterminding a plan to complete the

occupation and political takeover of Korea. He was named the first Japanese

resident general of Korea in 1905. He was answerable only to the Japanese emperor

and had the power to control all the Korean foreign relations and trade. To fulfill

his duties and to keep order in the country, he was given total access to all Japanese combat troops stationed in Korea.

While still in Japan, Ito pressured the weak Korean government into signing the "Protectorate Treaty" on November 19,

1905, which gave the Japanese the right to occupy Korea. After signing the treaty

as resident general, Ito made every effort to keep it a secret from the Korean people.

Following the ratification of the treaty, 12 Japanese commissioners were assigned to the various provinces in Korea,

with one being stationed in Seoul. Later, in March 1906, Ito arrived in Korea

to take the reins of power. At this time he ordered all foreign delegations in

Korea to withdraw. This action left Korea at the mercy of the Japanese. The new Japanese puppet government enacted laws that allowed Korean land to be sold

to Japanese, although land generally was just taken.

|

| Korean Emigrant village, Kando, Manchuria |

The Korean people were extremely

irritated under these grim circumstances. Word soon leaked out concerning

the Protectorate Treaty, provoking a wave of anti-Japanese violence. Several

small guerilla groups were formed and attacked the Japanese occupation forces. One

such group in Chungchong Province armed themselves with 50 cannons and conducted a long campaign of hit-and-run actions against

the Japanese. They were finally defeated, however, as most other groups

were, when hunted down by the much larger Japanese army. The general wave of

unrest, however, continued to spread very rapidly.

Violence pervaded the general population, as many loyal Korean government officials committed suicide, and Korean

government officials who had signed the Protectorate Treaty were assassinated.

In the face of the oppression

that accompanied this Japanese annexation of Korea, An Jung-Geun went into self-exile in southern Manchuria. There he formed a small private guerilla army of approximately 300 men, including

his brother. This army conducted sporadic raids across the Manchurian border

into northern Korea, keeping a relentless pressure on the Japanese in this region.

The violent objection of the Korean population soon spread out of the country as well as into the upper levels of the

Korean government. The Japanese government was unnerved by the vocal, patriotic

Korean organizations, particularly those that had formed within the United States.

Those in power wanted to quell these anti-Japanese sentiments to avoid having other countries interfere with their

control of Korea. With this in mind, in March 1907, the Japanese government sent

an American citizen, D.W. Stevens, to the United States on a mission to distribute pro-Japanese propaganda to the American

public. Stevens had originally been hired by the Japanese to help set up the

resident general's government in Korea. While he was in San Francisco, Stevens

was assassinated by two outraged Korean patriots. Many other political leaders

were assassinated during this violent time, including Yi Wan-Yong, the man Ito had appointed as the premier of Korea after

he had forced the Korean emperor to install a new pro-Japanese cabinet.

|

| An Jung-Geun Interrogation in Lui-Shung Prison |

In June of 1907, the Korean

emperor, Ko-Jong, in an effort to break loose of the Japanese control, secretly sent an emissary to the Hague Peace Conference

to expose the Japanese aggressive policy in Korea to the world. When Ito found

out, he forced Ko-Jong to abdicate the Korean throne on July 19, 1907, and the Japanese officially took over the government

of Korea. Severe rioting, involving many Korean Army units, broke out all over

Korea. The Japanese responded by disbanding the Korean police force and the army,

except for the palace guard. The Korean Army troops then retaliated by attacking

the Japanese troops, but they were quickly defeated. All Korean prisons, courts,

and police units were officially turned over to the Japanese government.

Even after the defeat of the Korean troops, resistance from the general Korean public continued for many years with

many guerilla groups operating out of southeastern Manchuria. Small groups of

patriots attempted assassinating several Japanese leaders and members of the Japanese-Korean government. Because of its proximity to Manchuria, the town of Kando in northern Korea became a hotbed of such activity,

and Hirobumi Ito decided to set up a significant Japanese military and police presence in the area. However, 20 percent of the 100,000 residents of Kando were Chinese.

When the Japanese began to crack down on the population of Kando, these Chinese were caught in the violence. The situation caused considerable conflict between the Japanese and the Chinese.

|

| Japanese Troops in Seoul |

In response to the increased

Japanese activity in the Kando region, An Jung-Geun led his guerilla army on a raid there in June 1909. The raid was a success, resulting in many Japanese deaths. Despite

such guerilla activities, the Japanese finally arrived at an agreement with the Chinese.

The treaty, signed on September 4, 1909, allowed the Japanese to build a branch line to the Southern Manchurian Railway

in order to exploit the rich mineral resources in Manchuria. In return, the Japanese

turned over to the Chinese the territorial rights to Kando. This brazen act of

selling Korean territory to another country was the last straw for many loyal Koreans such as An Jung-Geun. He set out for his base of operations in Vladivostok, Siberia, to prepare for his assassination of Hirobumi

Ito.

Russia was becoming very nervous at the level of Japanese activity in the northern Korean area and Japan's obvious

designs on Manchuria. Ito, who had officially become the president of the Japanese

Senate (an aristocratic government body), arranged to meet with Russian representatives at Harbin, Manchuria, to calm their

fears over the Japanese intentions to annex Manchuria and invade China. The final

plans for the meeting between Ito and General Kokotseff, a minister-level Russian government official, were set for October

26, 1909.

|

| Hirobumi Ito at Harbin Station just before his Assassination |

When Ito arrived at the Harbin

train station at 9:00 a.m. on October 26, 1909, An Jung-Geun was waiting for him. Knowing

full well that he would never escape alive, and that torture awaited him if captured by the Japanese, An Jung-Geun shot Ito

after he stepped off the train. Following the assassination, An was captured

by Japanese troops and imprisoned at Port Arthur. While in Japanese prisons,

he suffered through five months of extremely barbarous torture. Despite

this unbelievable treatment, it is said that his spirit never broke. On March

26, 1910, at 10:00 a.m., An was executed at Lui-Shung prison.

The assassination of Hirobumi Ito, like so many other actions by Korean patriots, only seemed to fuel the fires of

Japanese oppression. In 1910, the office of resident general, with Ito's successor

now in charge, was changed to governor general in order to allow a more dictatorial approach to the total control of Korea. Akashi Genjiro was then named as the commander of the Japanese military and police

superintendent in Korea. He launched an extremely harsh campaign to harass the

Korean population. He closed all newspapers, disbanded all patriotic organizations,

arrested thousands of Korean leaders, and enforced a strict military rule of the capital city of Seoul by crack Japanese

combat troops. This type of rule under the Japanese continued in Korea until

Japan surrendered at the end of World War II.

The sacrifice of An Jung-Geun

was one of many in this chaotic time in Korean history. His attitude and that

of his compatriots symbolized the loyalty and dedication of the Korean people to their country's independence and

freedom.

|

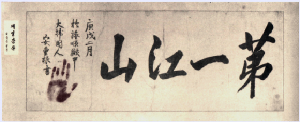

| Calligraphy by An Jung-Geun, |

Mr. An's love for his country was forever

captured in the calligraphy he wrote in his cell in Lui-Shung Prison prior to his execution. It simply

said, "The Best Rivers and Mountains." This implied that he felt his country was the

most beautiful on earth. Although his roles spanned from educator to guerilla leader, he was, above all,

a great Korean patriot.

|