|

The pattern Chung-Mu consists of 30 movements and is required

for advancement from 1st geup (high red belt) to 1st dan (black belt). This pattern

is named for Chung-Mu, the honorary title given to the great Admiral Yi Sun-Sin (1545-1598) of the Yi Dynasty. He was reputed to be the inventor of the first armored battleship (Geobukseon) in 1592, which is said

to be the precursor of the present-day submarine. His regrettable

death is symbolized in the end of this pattern with a left-hand attack. Checked

by the forced reservation of his loyalty to the king, Yi Sun-Sin was given no chance in his lifetime to show his unrestrained

potentiality.

|

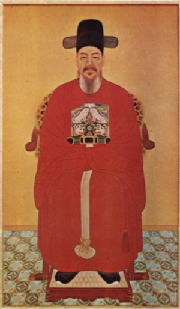

| Admiral Yi Sun-Sin |

Born in 1545, Yi Sun-Sin is

reputed to have been a master naval tactician; his prowess was largely responsible for the defeat of the Japanese in 1592

and 1598. He has been compared to Sir Francis Drake and Lord Nelson of England. His name is held in such high esteem that when the Japanese fleet defeated the Russian

navy in 1905, the Japanese admiral was quoted as saying, "You may wish to compare me with Lord Nelson but do not compare me

with Korea's Admiral Yi Sun-Sin. . . . He is too remarkable for anyone."

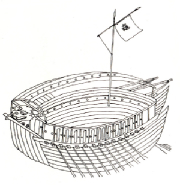

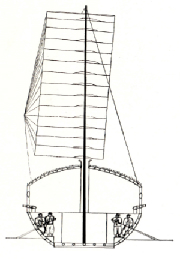

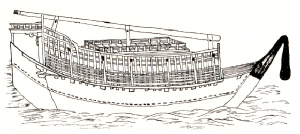

Yi Sun-Sin's most famous invention was the geobukseon, or turtle-boat, a galley ship decked over with iron plates to

protect the soldiers and rowing seamen. It was so named because the curvature of the iron plates covering the top decks

made it resemble a turtle's shell. The ship was 110 feet long and 28 feet wide with a lower deck for cabins and supplies,

a middle deck for oars-men, and an upper deck for marines and cannons. Most of the timber was 4-inches thick, giving the ship

protection from arrows and musket balls. It had a large iron ram in the

shape of a turtle's head with an open mouth from which smoke, arrows, and missiles were discharged. Another such opening in the rear and six more on either side were for the same purpose. The armored shell was fitted with iron spikes and knives that were covered over with straw or grass to

impale unwanted boarders.

|

| Drawing of the Geobukseon |

|

|

| Cross-Section of the Turtle Boat |

|

The geobukseon was not only

impervious to almost any Japanese weapon, but it was heavier and built for speed, and could overtake anything afloat. The ship carried approximately 40 3-inch

cannons that fired shot or steel-headed darts, and had hundreds of small holes for firing arrows or throwing bombs. In comparison, the Japanese ships usually carried one cannon, many muskets, and no protective armor. The geobukseon was, therefore, very effective in chasing down and sinking large numbers

of Japanese troop and supply ships as well as successfully attacking numerous heavy Japanese battleships head on. It was the most highly developed warship of its time.

|

| "Black" mark cannon used by Geobukseon (shot lead-balls or bundles of arrows) |

|

|

| "Wiwow" cannon used by the Geobukseon (came in long, medium, and short range version) |

|

|

| "Tiger" cannon used by the Geobukseon (shape of a crouching Tiger) |

|

The geobukseon was constructed in a critical period in Korean history, one of the many times Korean and Japanese

destinies converged. When Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the shogun of Japan, rose

to power in 1590, he decided to control the internal feuding in Japan. Because

Japan's largest threat was the other powerful warlords of Japan, he planned to tie up the financial resources of

the lords with an invasion of China and thereby dilute their power. He requested that Korea aid him in his conquest; when

it refused, he ordered two of his generals, Kato Kiyomasa (the Buddhist commander) and Konishi Yukinaga (the Christian commander),

to attack Korea in April 1592. The Japanese invasion force comprised 160,000 regular army troops; 80,000 bodyguard

troops; 1,500 heavy cavalry; 60,000 reserve troops; 50,000 horses; 300,000 firearms; 500,000 daggers; 100,000 short swords;

100,000 spears; 100,000 long swords; 5,000 axes; and 3-4,000 boats (40-50 feet by 10 feet).

The army was also supported by another 700 ships, transport vessels, naval ships, and small craft manned by 9,000 seamen. Having been acquainted with the use of firearms since 1543, the Japanese had imported

a large number of muskets from Europe, and had developed the ability to manufacture them four years before the first invasion.

|

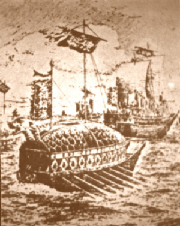

| Japanese Man-of-War, 16th Century |

The Koreans, on the other

hand, had few firearms, and did not know how to use or manufacture them. Outnumbered

and armed only with swords, bows and arrows, and spears, the Korean military was severely disadvantaged in the face of

the Japanese invading army armed with 300,000 muskets. Although a few courageous Korean

units resisted, such as those under the command of General Kim Si-Min, the army of Japan reached Seoul in just 15

days and had occupied the entire country by May 1592. The Korean king, Son-Jo,

fled with his court to Uiju in the Northern Provinces and sought aid from the Ming emperor of China with whom the Koreans

had several treaties.

|

| Painting of the Hideyoshi Invasion |

When the Ming armies joined in the fight, the tide of the war shifted away from the Japanese. They had to fight Korean guerilla groups as well as the Ming army, while at the same time finding that

they were cut off from their supplies by a Korean admiral named Yi Sun-Sin. Disease, malnutrition, and the cold soon

took its toll on Japanese morale. Having lost the will to fight, retreating

Japanese forces were stalked by guerilla forces led by Confucian scholars and Buddhist monks. Peace negotiations eventually took place between the Ming general and the Japanese. However, these talks dragged on for five years and reached no conclusion.

|

| Construction of the Geobukseon |

In early 1592, at the outset

of this conflict, Admiral Yi Sun-Sin, in charge of the Right Division of Chulla Province, made his headquarters in the

port city of Yosu. There he constructed his famed turtle ships. The first geobukseon was launched and outfitted with cannons

only two days before the first Japanese troops landed at Pusan. In the fifth

month of 1592, assisted by the admiral of the Left Division of Chulla Province, Won-Kyun, Admiral Yi engaged the Japanese

at Okpa. In his first battle, Admiral Yi commanded 80 ships compared to the Japanese

naval force of 800 ships. The Japanese were trying to re-supply their northern

bases from their port at Pusan. By the end of the day Yi had set afire 26 Japanese

ships and the rest had turned to flee. Giving chase, he sank many more, leaving

the entire Japanese fleet scattered.

Several major engagements followed, in which Admiral Yi annihilated every Japanese squadron he encountered. Courageous and a tactical genius, he seemed to be able to outguess the enemy. In one incident, Admiral Yi dreamt that a robed man called out "The Japanese are coming." Seeing this as a sign, he rose to assemble his ships, sailed out, and surprised a large enemy fleet. He burned twelve enemy ships and scattered the rest.

In the course of the battle, he demonstrated his bravery by not showing pain when shot in the shoulder. He revealed his injury only when the battle was over, at which time he bared his shoulder and ordered that

the bullet be cut out.

|

| Painting of the Korean Turtle Boat Fleet going into Battle |

|

| Turtle Boat Fleet Painting in Detail |

In August of 1592, 100,000

Japanese troop reinforcements headed around Pyongyang peninsula to head up the west coast.

Admiral Yi and his Lieutenant Yi Ok-Keui confronted them at Kyonnarang among the islands off the southern coast of

Korea. Pretending at first to flee, Admiral Yi then turned and began to ram the

Japanese ships. His fleet followed his lead and sank 71 Japanese boats. When a Japanese reinforcement fleet arrived, Admiral Yi's fleet sank 48 more Japanese

ships and forced many more to be beached as the Japanese sailors tried to escape on land.

This engagement is considered to be one of history's greatest naval battles.

Unaware of this battle, the Japanese commander had sent a message to the Korean King Son-Jo that read: "A 100,000 men

are coming to reinforce me. Where will you flee then?" Upon hearing that Admiral Yi had shattered the Japanese fleet, the king was elated and heaped all possible

honors upon him. For the Japanese, any hope of an invasion of China was now totally

crushed.

|

| Painting of the Geobukseon in Battle |

Admiral Yi Sun-Sin pushed on to Tanghang Harbor where he encountered another large Japanese fleet that included the

huge Japanese flagship of the Japanese admiral. Admiral Yi ordered his best archer

to shoot the Japanese admiral, who sat on the deck dressed in silk and gold. The

arrow pierced the Japanese admiral's throat, throwing the entire Japanese fleet into a panicked retreat which ended in carnage

as Yi pursued in his usual fashion.

In a brilliant military move,

Admiral Yi took the entire Korean Navy, 180 small and large ships, and sailed right into the Japanese home port at Pusan harbor

and attacked the main Japanese naval force of more than 500 ships, which was still at anchor.

Using fireboats and strategic maneuvering, he sank over half of the Japanese vessels.

However, receiving no land support, Admiral Yi was forced to withdraw. With

this battle, Admiral Yi completed what some naval historians have called the most important series of engagements in the history

of the world.

During one patrol sweep, Admiral Yi's fleet spotted 26 Japanese ships on the horizon.

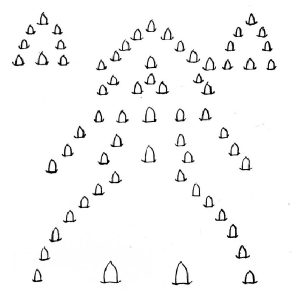

He spread out his forces in a formation known as the fishnet and advanced. The

fishnet or inverted V grouped the heaviest ships of the fleet at its vortex. As

the enemy ships were forced inside the V they were trapped and destroyed by Yi's heavy ships.

On this occasion the enemy entered into the V and before long was surrounded and all boats were burned.

|

| Korean Fleet Battle Formation |

|

|

| Japanese Fleet Battle Formation |

|

Korean control of the sea,

under the command of Admiral Yi Sun-Sin, soon forced the Japanese invasion to a complete standstill. Although the Japanese ground commanders begged for supplies, neither supplies nor reinforcements could

get past Admiral Yi Sun-Sin to reach the Japanese forces along the western coast of the peninsula. Because of this situation, the following months saw little military action.

|

| Screen Painting of a Geobukseon |

During his forced idleness Admiral Yi Sun-Sin prepared for the future; he had his men make salt by evaporating seawater,

and used it to pay local workers for building ships and barracks and to trade for materials his navy needed. His energy and patriotism were so contagious that many worked for nothing. Having heard not only of Yi's

military feats, but his contributions to the navy as well, the king conferred upon him the admiralty of the surrounding

three provinces.

For a successful invasion

of Korea, the Japanese knew that they would have to eliminate Yi Sun-Sin. No

Japanese fleet would be safe as long as his turtle boats were prowling the sea.

Seeing how the internal court rivalries of the Koreans worked, the Japanese devised a plan. A Japanese soldier named Yosira was sent to the camp of the Korean general, Kim Eung-Su, and convinced

the general that he would spy on the Japanese for the Koreans. Yosira

spent a long time acting as a spy and giving the Koreans what appeared to be valuable information. One day he told

General Kim that the Japanese General Kato would be coming on a certain date with a great Japanese fleet, and insisted

that Admiral Yi be sent to lie in wait and sink it. General Kim agreed and

requested King Son-Jo for permission to send Admiral Yi. The general was

given permission, but when he gave Admiral Yi his orders, the admiral declined. Yi

knew that the location given by the spy was studded with sunken rocks and was very dangerous.

|

| Replica of the Geobukseon |

When General Kim informed the king of Admiral Yi Sun-Sin's refusal to go, Admiral Yi's enemies at court insisted on his replacement by Won-Kyun and his arrest. As a result, in 1597 Admiral Yi Sun-Sin was relieved of command, placed under arrest,

taken to Seoul in chains, beaten, and tortured. The king wanted to have Admiral

Yi put to death, but the admiral's supporters at court convinced the king to spare him due to his past service record. Spared the death penalty, Admiral Yi was demoted to the rank of common foot soldier. Yi Sun-Sin responded to this humiliation as a most obedient subject, going quietly

about his work as if his rank and orders were totally appropriate.

With Admiral Yi stripped of

any influence, when negotiations broke down in 1596 Hideyoshi again ordered his army to attack Korea. The invasion came in the first month of 1597 with a Japanese force of 140,000 men transported to Korea

in thousands of ships. Had Admiral Yi been in command of the Korean Navy at that

time, the Japanese would most likely never have landed on any shore again. As

it was, however, the Japanese fleet landed safely at Sosang Harbor.

The spy Yosira now continued to urge General Kim to send the Korean Navy to intercept a fleet of Japanese ships. When ordered to do so, Won-Kyun gathered his 80 ships together and reluctantly set

sail. This fleet was hardly recognizable as Yi Sun-Sin's former one: Won-Kyun

had eliminated all of the rules and regulations set up by Yi when he took command as well as purging the ranks of all who

had been close to Admiral Yi. His inept maneuvers almost destroyed the entire

Korean fleet and alienated all his men. Consequently, this battle ended in a

complete defeat for the Korean Navy while Yi Sun-Sin was being detained as a foot soldier.

The Korean fleet scattered in a night storm and the main portion blundered upon the Japanese fleet the next day. On seeing the Japanese fleet, Won-Kyun panicked and retreated. He beached his boats and took to the land but the Japanese overtook and beheaded him. The Korean fleet scattered was mostly destroyed.

|

| Japanese Ships in Battle |

With the news of Won-Kyun's

disastrous defeat, a loyal advisor of the king called for Yi Sun-Sin's reinstatement.

Fearing for his country's security, the king hastily reinstated Yi Sun-Sin as the naval commander. In spite of his previous unfair treatment, Yi immediately set out on foot for his former base at Hansan. As he traveled, he met scattered remnants of his former force. By the time he arrived at Han-san he had only twelve boats but no lack of men, for the people all along

the coast had flocked to him when they heard of his reinstatement.

Yi drew up his fleet of 12 boats in the shadow of a mountain on Chindo Island off the Myongyang straits. One night his scouts reported the approach of a Japanese fleet. As

the moon dropped behind the mountain, the Korean fleet of 12 ships was shrouded in total darkness. When the Japanese fleet of 133 ships sailed by in single file, Admiral Yi's forces gave a large shout and

fired point blank. Yi employed one of his tactics, the use of two-salvo fire,

which resulted in a continuous barrage, causing the Japanese to think that they had run into a vastly superior force. Their fleet scattered in all directions in a total panic. The next day several hundred more Japanese ships appeared and Admiral Yi, fearless as ever, made straight

for them. He was soon surrounded, but sank 30 Japanese boats. The remainder

of the Japanese fleet, recognizing the work of the famous Admiral Yi Sun-Sin, turned and fled. Admiral Yi gave chase, decimated the enemy, and killed the Japanese commander Madasi.

After this battle, Admiral

Yi returned to Han-san and once again began rebuilding the navy and making salt.

His former captains and soldiers came back to him in "clouds." With

his salt-making operations and the money collected as a toll from fleeing merchant ships, Admiral Yi purchased needed

supplies and materials such as copper used in making cannons and ships. He

again managed to establish a large, well equipped garrison.

Despite Admiral Yi's personal success, Korea was alone and in trouble. What

help was available was most often supplied by Chinese troops and naval units. Although

this military support was extremely welcome, it carried with it a new set of problems.

Often, these problems took the form of Korean fighting units having to put up with Chinese commanders being in charge

of them. These commanders were usually not inspired by the same patriotism that

the good Korean commanders were guided by.

In 1598, the Chinese emperor

sent Admiral Chil-Lin to command Korea's western coast. Admiral Chil-Lin was

an extremely vain man and would take advice from no one. Knowing this to be a

serious problem, Admiral Yi made every effort to win the trust of the Chinese admiral.

His political skills proved to be as good as his military ones. He allowed

Admiral Chil-Lin to take credit for many victories that really were his own. He

was willing to forgo the praise and let others reap the commendation in order to have the enemies of his country destroyed. Yi Sun-Sin was soon in charge of all strategy while Admiral Chil-Lin took the credit. This arrangement made the Chinese seem successful, which so encouraged them that they

gave Korea the aid it desperately needed. Admiral Chil Lin could not praise Admiral

Yi enough, and repeatedly wrote to the Korean King So-Jon that the universe did not contain another man who could perform

the feats that Yi Sun-Sin apparently found easy.

It is fitting that Admiral Yi died in battle in 1598. It was during the

time when the Japanese were trying to evacuate many of their forces. Admiral

Yi and the Chinese Admiral Chil-Lin swooped down on their forces and nearly wiped out the entire fleet. Yi Sun-Sin, while standing in the bow of his flagship directing the battle, was struck with a stray bullet. Before he died, he is quoted as saying, "Do not let the rest know I am dead, for it

will spoil the fight."

|

| Fire Arrows used by the Geobukseon |

During the second invasion

of Korea in 1597, the Japanese were only able to occupy Kyongsang and part of Chulla Provinces. Their efforts were thwarted by the harassment of the Korean volunteer army and the strategies of Admiral

Yi Sun-Sin that prevented them from landing or being supplied beyond the southern provinces.

Partly due to this lack of progress, the war ended after Hideyoshi's death late in 1598 when the Japanese troops were

recalled to Japan.

|

| Admiral Yi's Service Swords |

The six years of war, from 1592 to 1598, laid waste to the whole Korean peninsula.

Hardly a building still stands in Korea that predates the Hideyoshi invasions except for a few stone structures. Rare and valuable collections of books were destroyed, including the official records

of the reigns of the Yi Dynasty. A series of famines, epidemics, peasant revolts,

and a full-scale renewal of political squabbling in the Korean government followed on the heels of the war. As a result, culture and government were left in chaos and the social system of the country was disrupted.

For all its disastrous aftermath,

the war did provide Korea with one of its most celebrated national heroes, Admiral Yi Sun-Sin.

|

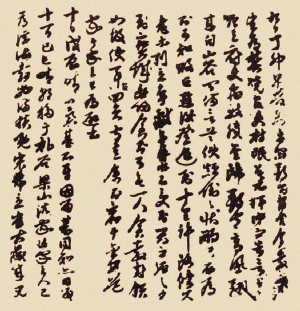

| Admiral Yi's War Diary |

Known primarily as an inventor of the world's first iron-plated vessel, and master tactician credited with having sunk

an unbelievable number of enemy vessels with only a small naval force, Yi also had other accomplishments. Some of his little-known inventions included the use of a smoke generator in which sulphur and saltpeter

were burned, emitting great clouds of smoke. This first recorded use of a smoke

screen struck terror in the hearts of the superstitious enemy sailors, and more practically, it masked the movements of Admiral

Yi's ships. Another of his inventions was a new Korean weapon, a type of flamethrower,

which was a small cannon with an arrow-shaped shell housing an incendiary charge. This

flamethrower successfully set afire hundreds of enemy ships.

Along with his inventions,

specific tactical maneuvers demonstrate Yi's brilliance as a naval tactician. One

such tactic was his defeat of a large enemy convoy by using a formation described as the fishnet, described earlier. Yi also used two-salvo fire against a large force of Japanese warships - an early,

if not first, use of such firepower.

|

| Pages from Admiral Yi's War Diary in his own hand writing |

Admiral Yi Sun-Sin was one of the greatest heroes in Korean history. He

was posthumously awarded the honorary title of Chung-Mu, "Loyalty-Chivalry," in 1643.

The Distinguished Military Service Medal of the Republic of Korea, the third highest, is named after this title. Numerous books praise his feats of glory, and several statues and monuments commemorate

his deeds. In April 1968, a 55-foot high statue of Yi (reportedly the tallest

in the Orient) was dedicated in Seoul, Korea. His statue on the peak of Mt. Nammang,

life-size, indicates that he was a very large man, as judged by the size of the sword on it.

The shrine of Chungnyolsa, meaning "faithful to king and country," established in 1606, is now both a museum

and shrine dedicated to the admiral. The eight relics on display in this shrine

were gifts to Admiral Yi Sun-Sin from the Chinese emperor and include a 7-foot commander's bugle, a 5-foot sword, a ceremonial

sword (weighing 66 pounds), Admiral Yi's seal, and several flags. Another

Korean treasure is the war diary of Admiral Yi Sun-Sin, which, in addition to some of his personal articles,

is preserved at the shrine of Hyonchungsa. In addition, a small museum in the

city of Chungmu, a traditional seaport named after him, displays a replica of the turtle ship as well as other articles of

that period.

Perhaps one of Yi Sun-Sin's greatest qualities was his drive to serve his king and

Korea in any way he could. When almost everyone in Korean politics and military service was forced to side

with one of the two powerful Korean political parties of the time to survive the ruthless atmosphere, Yi chose neither and

was only loyal to his king and country. Moreover, at a time in Korean history when position and rank meant

everything, Yi Sun-Sin demonstrated a remarkable ability to maintain his pride in the face of an unwarranted demotion.

Any other officer of his time would have been driven to suicide or revenge in an attempt to erase such a terrible disgrace.

Yi, however, merely went about his work as a common foot soldier without a thought for these courses of action.

Not only a naval innovator and tactician hundreds of years ahead of his time, Yi was also a man with bravery and loyalty

matched by few in the history of the world.

|