|

The pattern Yul-Gok consists of 38 movements and is required for advancement from 5th geup (high green belt) to 4th

geup (blue belt). This pattern is named for the pseudonym (Yi Yul-Gok) of the

great Korean philosopher and scholar Yi I (1536-1584). The 38 movements of this

pattern represent his birthplace on the 38th latitude. The diagram, or shape,

of this teul ( ± ) represents the Chinese character for scholar.

Born near the town of Kangnung

in Kwangwondo province, Yi I was fortunate to have a very talented and artistic mother, Sin Saim-Dang. She was unusually

accomplished for a woman of those times and was known as an excellent painter.

Well respected throughout Chulla and Kyongsang provinces during her lifetime, she has become more renowned throughout

the world in the last 300 years. It is most likely that her talent had a profound

effect on her son's upbringing; he is said to have been able to write characters

as soon as he could speak and to have composed an essay at the age of seven.

|

| Yi-I (Yi Yul-Gok) |

Being close to his mother, Yi I was very distressed when she died in 1559. According to some sources, it was

as a result of this grief that he took refuge in a Zen Buddhist monastery in the rugged and beautiful Diamond Mountains. During his one-year stay there, he meditated, reflected on Buddhist philosophy, and

became well-versed in Buddhist teachings. After leaving this monastery, he returned

to society and devoted his life to studying Confucianism. In later years, as

he developed into a renowned philosopher, he acquired the pseudonym Yul-Gok (Chestnut Valley).

Yul-Gok was well-known for

his development of a school of thought concerning the philosophy of the 12th century Confucian scholar Chu-Hsi. Chu-Hsi established the concepts of "li" (reason or abstract form) and "chi" (matter

or vital force). He proposed that these two concepts were responsible

for all human characteristics and the operation of the universe. As he defined

the concepts, they are very similar to the concepts of body and soul in Western philosophy and religion. The "li," however, is not totally synonymous with the idea of an individual

soul but instead represents groups or models for each form of existence. Yul-Gok's

school of thought supported the concept that the "chi" was the controlling agent in the universe and that the "li" was a supporting

component. Experience, education, and practical intellectual activities were

stressed in this school of thought. The other major school of thought stemming

from the philosophy of Chu-Hsi was fostered by Yi Hwang (Yi Toe-Gye), who proposed that the "li" controlled the "chi" and

stressed the importance of moral character building.

|

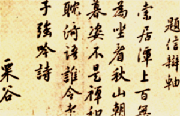

| Handwriting of Yi Yul-Gok |

This school of thought was carried over into Yi-I's personal life. In

fact, he took sincerity very seriously; "A sincere man," he felt, "was a man that knew the realism of heaven." He once wrote that a house could not sustain harmony unless every family member was sincere. He felt that when confronted with misfortune, a man must carry out a deep self-reflection to find and correct

his own mistakes. In addition to his commitment to society, Yul-Gok emphasized

the value of practical application. The reason for study, he asserted, was to

apply the knowledge one has gained. As an example of his dedication to this belief,

he is said to have manufactured his own hoes and worked at the bellows, which was not usually done by a person of his stature. This attitude toward life was consistent with his concern for the improvement of the

individual as well as for society as a whole.

His concern for sincerity, loyalty, and the improvement of the individual was manifested in his own actions

toward others. Yi's stepmother enjoyed drinking wine, a practice Yul-Gok never

approved of. Every morning, year after year, he brought her several cups of wine,

never reproaching her for her habit. Finally, she decided on her own to stop

drinking without ever having been told of his displeasure. In gratitude for those

years of non-judgmental dedication, Yul-Gok's stepmother clad herself in white mourning attire for three years after his death.

|

| Yi Hwang (Yi Toe-Gye) |

Yul-Gok was also deeply involved in government and public affairs. He

passed the state examinations at the very young age of 24 and was ultimately appointed to several ministerial positions including

that of Minister of Defense. He did more for establishing a mechanism to obtain

the opinion of the common people, a national consensus, than any man in Korean history.

Popular opinion of the masses, he felt, must arise spontaneously from the total population. He knew that the survival and vitality of a kingdom depended directly upon whether public opinion was obtained

from all sections of the population. Yul-Gok felt that public resentment could

be directly attributed to misrule. Rulers should, therefore, pay closer heed

to the voices of their subjects. He was convinced that when impoverished people

are deprived of their humanity, morality crumbles and penal systems are rendered ineffective.

Because of his beliefs and his fear for the survival of the kingdom, Yul-Gok initiated many attempts at government

reform. In one such effort, Yul-Gok sought to establish local government structures

that were based on an education according to the philosophy of Chu-Hsi. He drew

up a set of village articles (Hyangyak) designed to instruct the villagers of Haeju in Confucian ethics. This government, however, was run by the elite class (Yangban) and ultimately failed due to corruption.

Yul-Gok was also the first

to propose the Taedong (Great Equity) System for solving the financial crisis of the Korean government. Under the Taedong

System, taxes would be levied on land rather than on households, and the government would be required to purchase local

products with tax dollars.

In addition to his active involvement, Yul-Gok was also inadvertently pulled into a serious political squabble by virtue

of his philosophy. In 1575, the Korean government became mired down in a

political stalemate that ultimately contributed to its inability to repulse the invasion by Japan some ten

years later. Two distinct factions, polarized within the Korean government, were

constantly at each other's throats. These factions originally arose as a result

of a personal quarrel between two men, Sim Ui-Gyom and Kim Hyo-Won. Ultimately,

every official in the government had to align himself with one side or the other or risk attack by both. Since Kim's residence was in the Eastern quarter of Seoul and Sim's was in the western quarter, these two

factions became known as the Easterners and the Westerners, respectively. This

feuding continued long after Kim and Sim had disappeared from public life, and often took the guise of schemes designed to

have members of the rival faction exiled, removed from office, or executed on false charges.

These two factions were not only at odds politically but soon became philosophically opposed, with the easterners following

the teachings of Yi-Hwang and the western faction following the teachings of Yul-Gok.

These philosophical differences tended to drive the two factions further apart, increased the conflicts, and made the

functioning of government virtually impossible.

In 1583, a year before his death, Yul-Gok proposed that the government train and equip a 100,000-man Army Reserve Corps. This suggestion, like others he recommended, was undermined by minor officials who

were caught up with the east-west political conflict within the government. It

was very unfortunate that this suggestion concerning national security was never allowed to be implemented. Nine years later, the Korean military forces and government officials failed totally in their resistance

against the invasion by the Japanese army of Hideyoshi, resulting in the occupation of Korea.

Although never really permitted

to see his theories and systems applied due to the political environment of the time, Yul-Gok nonetheless was an extraordinary

philosopher. Long after his death in 1584, Yul-Gok has continued to have a profound effect upon Korea and

the world as a result of his lifelong dedication to Confucianism and theory of government.

|