|

The pattern Do-San consists of 24 movements and is required

for advancement from 7th geup (high yellow belt) to 6th geup (green belt). This

pattern is named for Do-San, the pseudonym of the Korean patriot An Chang-Ho (1876-1938).

Throughout his life, An Chang-Ho was a driving force in the Korean Independence Movement. He was particularly committed to preserving the Korean educational system during the Japanese

occupation, and he was well known for sincerity and lack of pretense in dealing with others.

|

| An Chang-Ho |

To understand the significance of An Chang-Ho's achievements, one must understand the oppressive climate throughout

the Korean peninsula during the Japanese occupation (1904-1945). During this

occupation, an effort was made to eradicate the Korean culture, literature, historical records, and education. As a result of this oppression, many refugees fled to China, Manchuria, the United States, and other countries. Among the first Koreans to immigrate to the United States in 1903 were An Chang-Ho

and Rhee Syng-man, who was later to become the first president of the Republic of Korea.

Once in the United States, An Chang-Ho established groups within the Korean community in support of the independence

of the Korean people. Similar groups were simultaneously being organized in other

countries by other Korean patriots. Religious organizations from various

countries lent valuable assistance to these groups.

In 1907, An Chang-Ho returned

to Korea to establish the Sin-min-hoe (New People's Society), a secret independence group in Pyong-An Province. The Sin-min-hoe was associated with Protestant organizations and supported a

youth group and a school. The organization was dedicated to promoting the recovery

of Korean independence through the cultivation and emergence of nationalism in education, business, and culture.

In 1908, the Sin-min-hoe established the Tae-song (Large Achievement) School to provide Korean youth with an education

based on national spirit. The political environment of the time, however, was

not conducive to the founding of such a school; the Japanese were in the process

of actively banning education for Koreans. By denying the Korean children proper

schooling, the Japanese wanted to ensure their illiteracy, thus essentially creating a class of slave workers.

|

| Koreans Prisoners being tortured |

|

| Members of the Korean Independence Army taking an Oath before battle |

By 1910, the Sin-min-hoe had

around 300 members and represented a threat to the occupation. The Japanese were

actively crushing these types of organizations, and the Sin-min-hoe quickly became a target of their efforts. An opportunity to break up the Sin-min-hoe soon presented itself.

In December of 1910, the Japanese governor general, Terauchi, was scheduled to attend the dedicating ceremony for the

new railway bridge over the Am-nok River. The Japanese used this situation to

pretend to uncover a plot to assassinate Terauchi on the way to this ceremony. All

of the Sin-min-hoe leaders and 600 innocent Christians were arrested. Under severe

torture, which led to the deaths of many, 105 Koreans were indicted and brought to trial.

During the trial, however, the defendants were adamant about their innocence.

The world community felt that the alleged plot was such an obvious fabrication that political pressure grew, and most

of the defendants had to be set free. By 1913 only six of the original defendants

had received prison sentences.

|

| Members of the Korean Righteous Army |

|

| Korean Liberation Army formed in China |

By this time, the Japanese had become fairly successful at detecting and destroying underground resistance groups. They were not at all successful, however, in quelling the desire for freedom and self-government

among the Korean people. The resistance groups moved further underground and

guerilla raids from the independence groups in Manchuria and Siberia increased. The

Japanese stepped up their assault on the Korean school system and other nationalistic movements. After the passage of an Education Act in 1911 the Japanese began to close all Korean schools. In 1913 the Tae-song School was forced to close, and by 1914 virtually all Korean schools had been shut

down. This all but completed the Japanese campaign of cultural genocide. Chances of any part of the Korean culture surviving rested in the hands of the

few dedicated patriots working in exile outside of Korea. By the end of World

War I, one of these freedom fighters, An Chang-Ho, had returned to the United States with Rhee Syng-man. There, Rhee had organized the Tong-ji-hoe (Comrade Society) in Honolulu, and An Chang-Ho had formed the

Kung-min-hoe (People's Society) in Los Angeles. Through these and other organizations,

an attempt was made to pressure President Woodrow Wilson into speaking in behalf of Korean autonomy at the Paris peace talks. Finally, in 1918, a representative of the Korean exiles was sent to these peace talks.

|

| Rhee Syngman |

In 1919, Rhee Syngman, An

Chang-Ho, and Kim-Ku set up a provisional government in exile in Shanghai. They

drew up a Democratic Constitution that provided for a freely elected president and legislature. This document also established the freedom of the press, speech, religion, and assembly. An independent judiciary was established, and the previous class system of nobility was abolished.

Finally, on March 1, 1919, the provisional government declared its independence from Japan and called for general resistance

from the Korean population. During the resistance demonstrations, the

Japanese police opened fire on the unarmed Korean crowds, killing thousands.

Many thousand more were arrested and tortured.

|

| Painting of the Independence Movement in Pagoda Park March 1, 1919 |

|

| Leaders of the Samil Independence Movement |

Even after the Korean Declaration of Independence, An Chang-Ho continued his efforts in the United States on behalf

of his homeland. In 1922, he headed a historical commission to compile all materials

related to Korea, especially the facts concerning the Japanese occupation.

|

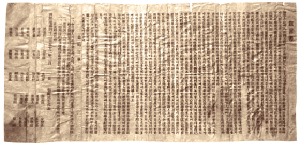

| Korean Declaration of Independence |

Korean culture owes much to An Chang-Ho. His dedication to the education

of the Korean people and to the protection of its culture was vital during a time when the Japanese were attempting to eradicate

Korean culture and independence.

|