|

The pattern Won-Hyo consists of 28 movements and

is required for advancement from 6th geup (green belt) to 5th geup (high green belt). This pattern is named

for the Buddhist monk Won-Hyo (617-686 A.D.), who is credited with having completed the introduction of Buddhism to the general

population of the kingdom of Silla just prior to his death.

Won-Hyo,

born in northern Kyongsang Province, was said to be wise from birth. As legend has it, he was

born in a forest in Chestnut Valley under a sal tree. The sal tree is significant, as reference

to it is usually only found in the legends of very revered figures.

|

| The Buddha at Popjusa Temple |

Won-Hyo's official name, given to him at birth,

was Sol-Se-Dang. He derived the pen name Won-Hyo, meaning "dawn," from his nickname "Se-Dak,"

which had the same meaning. He assumed this pen name in later years after he had become more accomplished

as a Buddhist philosopher and poet. In the past, Koreans were identified by many names; each

person had a nickname as well as an official name. A person of intellectual or artistic talents might also

be given a pen name, and monks and apprentices were often given yet another name by their masters.

Won-Hyo

started his career at the age of 20 when he decided to enter the Buddhist priesthood and converted his own home into a temple.

Buddhism, however, was not a popular religion in Silla at that time. Although this religion had

been introduced into the kingdom of Goguryo in 372 A.D. and Baekje in 384 A.D., the general population of Silla was reluctant

to accept it. The monk A-Tow was supposed to have introduced it to Silla between 417 A.D. and 457 A.D.,

but the religion was mainly confined to the royal family and rejected by the people.

|

| Pulguksa Temple |

This religious isolation, however, was to change during

the 7th century. At that time, Silla was at war with the kingdoms of Baekje and Goguryo. It

was under constant invasion from Baekje, and in the year 642 A.D., it lost 40 castles to Baekje attacks, including the great

castle of Taeya near the capital of Silla. This atmosphere dramatically influenced the Buddhist faith of

all three kingdoms. Religion became more nationalistic, which tended to intensify the ferocity of the conflicts.

|

| Naksamsa Temple |

|

| Dabotap Pagoda in Popjusa Temple |

In order to accelerate the

development of this type of national spirit in Silla, King Pop-Hung wanted to officially recognize Buddhism in 527 A.D. He tried to establish it as an official state religion in the area around Gyongju. The attempt was met with vehement opposition by members of the court. However, in 528 A.D., these members of the court pressured the King into agreeing to the execution of a

22-year old monk named Ichadon to convince them that Buddhism was a worthwhile religion.

Ichadon's death for his belief in Buddhism resulted in stories of his blood being white as milk at the execution. These stories made him a martyr to this cause, and the King issued a royal mandate

that granted freedom of Buddhist belief. Shortly afterward, Buddhism was accepted

by the people. Ichadon was named as one of the ten sacred monks of Silla by King

Hun-Duk in later years, but the study of Buddhism during the reign of King Pop-Hung required the ability to read and

write Chinese. Therefore, serious study was still confined mainly to the monks

and the aristocratic population

|

| Hwaomsa Temple |

Unfortunately, not many places were open for the serious

Buddhist student to study in Silla. Therefore, Won-Hyo and the noted monk Ui-Sang, like other monks

of the time, set out to study Buddhism in China in 650 A.D. The overland journey took

them to Liaotung in Goguryo. Mistaken as spies along the way by several Goguryo sentries, they barely

escaped captivity and were able to return to Silla. There is no further record of Won-Hyo traveling to

China to study although one more attempt was made shortly after Baekje was defeated in 660 A.D. by Silla and Tang troops from

China. Such study was not necessary however, because wisdom was Won-Hyo's from birth and he did not

need a teacher. He therefore became the only monk of his time who did not study in China.

|

| Four-Lion Pagoda in Hwaomsa Temple |

The

many monks who did study in China had a broad impact on the religious culture of the Korean peninsula.

In fact, there were at least five main sects of Buddhism being practiced in Silla during this period:

Kyeyul, Yulban, Chinpyo, Popsong, and Hwaom. Chinpyo and Popsong were introduced by Won-Hyo with

Popsong being based on his book, Sipmun Hwajongnon

(Treatise on the Harmonious Understanding of the Ten Doctrines), from which Weon-Hyo's posthumous title of "Hwaong

Guksa" was derived. Won-Hyo was, in fact, the most influential of the many monks of the 7th century.

He used his power in an attempt to unify the five existing sects and reduce their constant sectarian

rivalries. He is also considered to be one of the most prolific writers in all of the Buddhist

countries of his time. His works include over 100 different kinds of literature consisting of about 240

volumes. Unfortunately, only 20 works within a total of 25 volumes have survived. One

of the forms he chose to use was a special Silla poetic form, Hyangga. These poems were mainly written

by monks or members of the Hwarang concerning patriotism, Buddhism, and praise of the illustrious dead.

Won-Hyo's poem "Hwaomga" is said to be among the most admired of these poems.

Won-Hyo's writing was not the only area in which

he gained recognition. He was well known both to the general population and to the members of the royal

family and their court. He was often asked to conduct services, recite prayers, and give sermons at the

royal court. In 660 A.D., King Mu-Yol became so interested in Won-Hyo that he asked him to come and live

in the royal palace of Yosok. A relationship with the royal princess Kwa developed and was soon followed

by their marriage and the birth of their son Sol-Chong.

Sol-Chong grew up to become one of the ten Confucian sages of the Silla era.

He is recognized for his scholarship in Chinese literature and history, and for his adaptation of Idu, the system of

using Chinese characters phonetically to record Korean songs and poems. As Korea

had not yet developed an alphabet this adaptation was very important. It made

Chinese literature available to the general public by creating, in effect, a method for translation. Sol-Chong is said to have been the author of many original works; however his Kye-Hwa-Wang is his only

surviving work.

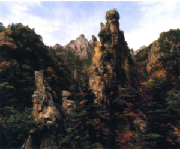

|

| Mount Kumgang, where Weon-Hyo taught |

Shortly after his son was born, Won-Hyo left the palace

and began traveling the country. In 661 A.D., he experienced a revelation in his Buddhist philosophy and

developed the Chongdo-Gyo (Pure Land) sect. This sect did not require study of the Chinese Buddhist literature

for salvation, but merely diligent prayer. His belief was that one could obtain salvation, or enter the

"Pure Land," by simply praying. This fundamental change in Buddhist philosophy made religion

accessible to the lower classes. It soon became very popular among the entire population. And,

in 662 A.D., Won-Hyo left the priesthood and devoted the rest of his life to traveling the country teaching this

new sect to the common people.

Won-Hyo's

contributions to the culture and national awareness of Silla were instrumental in the unification of the three kingdoms

of Korea. By 660 A.D., Baekje was defeated by the allied armies of Silla and the Tang Dynasty of China.

Later, in 668 A.D., the king of Silla, Mun-Mu, was finally successful in defeating the kingdom of Goguryo.

This victory was tainted, however, when the Tang troops set their goals on also conquering Silla. But,

in 677 A.D., after nine years of resistance, the Tang armies were driven from Korea and the unification of the three Kingdoms

of Korea was completed.

|

| Stone Pagoda in Punhwangsa Temple in Kyongju |

Won-Hyo

died in 686 A.D. and was laid in state by his son Sol-Chong in Punhwangsa temple. He had seen the unification

of the Three Kingdoms of Korea in his own lifetime and had helped to bring about a brilliant culture in Korea through his

efforts in Buddhist philosophy. He had a profound influence on quality of life in Silla and on Buddhism

in Korea, China, and Japan.

|